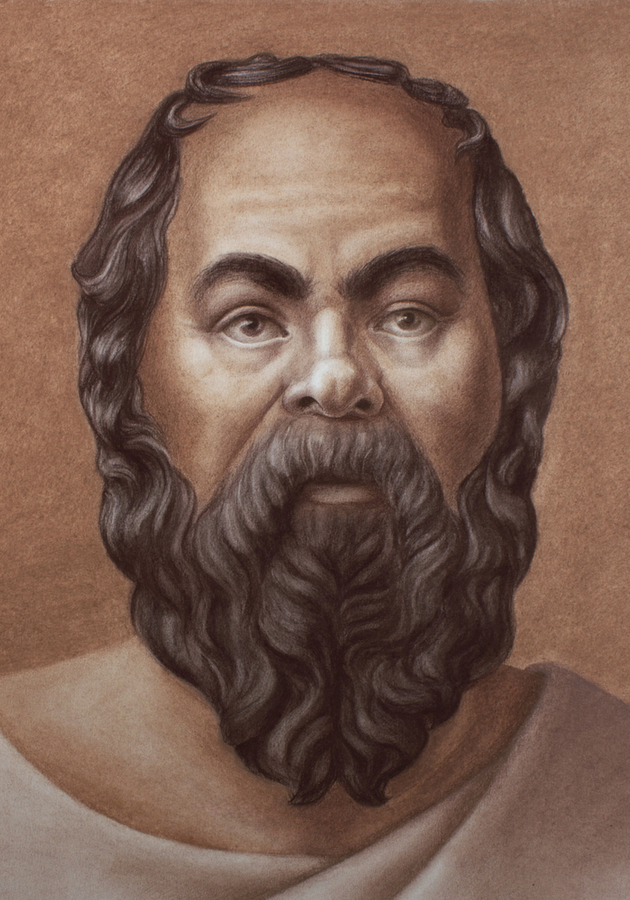

The first Ancient Greek philosopher to have left to posterity any sense of individual personality, Socrates is commonly considered one of the founders of Western philosophy and the central figure in the subsequent development of Europe’s rich intellectual tradition. Yet, he wrote nothing, established no school, and held no definite theories of his own. So, how did he get to be so influential? What is more, how do we know about him and his ideas in the first place? That is as good a place as any to begin our story of Socrates.

The sources for Socrates

In Plato’s late dialogue “Phaedrus,” Socrates disparages writing as an inferior art, describing it as “an elixir not of memory, but of reminding.” Moreover, he adds, writings are simultaneously rigid and indiscriminate, in that they say one and the same thing both to those who understand and those who have no interest in them. They are, essentially, just like paintings: as lifelike as they might seem at first glance, if you ask them a question, writings can do nothing more than preserve solemn silence and wait for their creator to come to their aid. For reasons such as this, concludes Socrates, the spoken word, the living dialogue, is far superior to dead writing: “Rather than on papyrus, it is written down, with knowledge, in the soul of the listener; it can defend itself; and it knows for whom it should speak and for whom it should remain silent.”

Owing to this belief, Socrates never wrote anything himself. And because he didn’t, we depend on others for our knowledge of him – his contemporaries, his followers and his enemies. In this regard, four names particularly stand out: Aristophanes, Xenophon, Plato, and Aristotle. “The only statement common to all four,” notes a modern historian of philosophy, “is that there was a philosopher called Socrates.” Even though anything beyond that remains speculative indeed, we can safely exclude Aristophanes’ comedy “The Clouds” from consideration, since the play gives a uniquely distorted picture of Socrates, characterizing him as some sort of a sophist who misguided the youth. Moreover, as great a playwright as he was, Aristophanes was a notoriously conservative thinker who favored the ways of the old and was against all reform and novelty.

Unlike Aristophanes, Xenophon was both a friend and a student of Socrates. Although he was otherwise a serious historian, his Socratic writings are mostly fictional and, in both style and mission, resemble historical novels much more than they do sincere testimonies or researched biographical accounts. Aristotle himself describes Xenophon’s “Symposium” and “Memories of Socrates” as “imaginary conversations in which Socrates becomes, more often than not, a mouthpiece for Xenophon’s own ideas.” Many say a similar thing regarding Plato’s late works, but Plato’s early and middle dialogues seem to give a credible historical account of Socrates. In most of them, Socrates is the main speaker, which makes it rather difficult to tell where Plato ends and Socrates begins. Even so, several of Plato’s Socratic dialogues – especially the “Apology,” the “Crito” and the “Phaedo” – are our main sources for the life, character and philosophy of Socrates.

The life of Socrates

According to 3rd-century biographer Diogenes Laërtius, when Socrates heard his pupil Plato reading one of his early dialogues out loud, he exclaimed: “By Heracles, what a number of lies this young man is telling about me!” Yet, in one of his late letters, Plato enigmatically remarked that “no writing of Plato exists or ever will exist, but those now said to be his are those of Socrates become beautiful and new.” Flummoxed by the astounding discrepancy between these two claims – which they usually refer to as the Socratic problem – modern historians of philosophy have made a habit of comparing Plato’s dialogues with other sources to draw conclusions about similarities and differences in the way Socrates is represented. The differences they’ve catalogued are too many to list here.

Indeed, whereas the Socrates of Aristophanes is an annoying nuisance, and that of Xenophon – a righteous teller of safe platitudes, Plato’s Socrates is an extremely original thinker with ideas capable of upsetting an entire civilization. It is mostly Plato’s storybook representation of Socrates that interests modern historians as it is the only one that constitutes a figure of everlasting philosophical significance. Since this representation is an expression of Plato’s personal understanding of an actual, real individual, it is only suitable to begin our discussion of Socrates with a brief biographical portrait more firmly rooted in historical research than in literary analysis.

Born in Athens in 469 B.C., Socrates was the son of a sculptor and a midwife. It is likely that he pursued his father’s profession while studying philosophy before being called up for military service. He made a reputation for himself as a soldier during the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. At the battle of Potidaea in 432 B.C., he saved the life of young Alcibiades who later became his lover, as well as a prominent Athenian general and statesman. At Delium in 424 B.C., Socrates is said to have been the last Athenian to give ground to the Spartans. If all Athenian soldiers possessed the valor of Socrates, went a popular 5th-century Greek saying, the Spartans would have surely lost the battle.

After returning to Athens from the war, Socrates worked as a stonecutter and statuary for a while. Second-century geographer Pausanias tells us that there stood, near the entrance to the Acropolis, two sculptures carved by him: a Hermes and the Three Graces. Nonetheless, when his father died, Socrates seems to have inherited just enough money to live with his bad-tempered wife Xanthippe and their three children without having to work. From then on, he became a familiar sight around Athens, involving himself in philosophical discussions with fellow citizens and gaining a following of young students. According to Socrates’ own testimony (as related by Plato in his “Apology”) a particular event had a transformative effect on his life and worldview. This event deserves a separate chapter.

Socratic method: genesis and overview

It all started when Chaerephon, an unusual and impetuous man born in the same year as Socrates, went to Delphi to ask the famous oracle who the wisest of all men in Greece was. The Pythian prophetess, echoing the words of the god Apollo, replied that there was none wiser than Socrates. When Chaerephon told this to Socrates, it left the philosopher quite perplexed. “What can the god mean?” he wondered. “What could be the interpretation of this riddle?” For Socrates knew that he had no wisdom, small or great. So, what could a god mean in saying that he was the wisest of all people? A god cannot lie, he knew, and Chaerephon swore to have relayed the truth. Moreover, he could have gained nothing from lying in the first place.

After long consideration, Socrates devised a method to test out the prophecy. He realized that if he could find someone wiser than himself, he could go to the Oracle of Delphi and say straightforwardly to the prophetess: “Here is a man who is wiser than I am.” So, accordingly, he went to a politician who had the reputation of wisdom and began a discussion with him. After posing him a few questions, however, he was surprised to discover that the man only thought that he knew things, when in reality he knew nothing. He repeated this experiment several times over only to realize that neither artisans nor poets knew more than him about anything other than the craft of making vases or verses. It was then that, in a flash of inspiration, Socrates finally deciphered the message of the gods.

He was deemed the wisest of all people not because he possessed some kind of wisdom which surpassed that of others, but because he was the only human alive to realize that God only can be considered wise, and that – compared to his – the wisdom of humans is worth little or nothing. Other people knew nothing but thought they knew a lot. Socrates was wiser than them because, at least, he knew that he didn’t know anything. Obedient to God, he made it his mission to make enquiry into the wisdom of anyone, whether citizen or stranger, conceited enough to deem themselves wise. By asking them simple yes or no questions, Socrates made a habit of showing that these individuals were just capable orators, putting on a show. As simple as it might seem, Socrates’ method of examining an argument from a position of ignorance was actually revolutionary.

Socratic irony: skepticism and dialectic

At the time Socrates began prowling among people’s beliefs and prodding them with questions, a group of divergent philosophers now known as Sophists were earning a lot of money by posing as itinerant, professional educators of young Athenians. Most of the Sophists presented themselves as specialists in several subject areas, as varying as philosophy, mathematics, rhetoric, and music. What Socrates set out to do was demonstrate that they were actually irreligious charlatans who mostly knew their way around words – and nothing more. His memorable aphorism that the only thing he knew was that he knew nothing was probably formulated as an ironic reproach of the apparent versatility and polymathy of the Sophists.

Unlike them, Socrates was not interested in arguing for the sake of making money. He was even less interested in winning arguments or imparting upon others some ready-made answers. His central and only concern was proper examination. Socrates was the first philosopher in history to realize that solving a problem is far less important than suitably investigating it. Hence, he was also the first one to understand that questions, if properly put forward, can constitute a vital part of any answer. It wasn’t answers, but questions that lay at the heart of Socrates’ philosophy. As Aristotle would later remark, pretty much the only thing Socrates ever invented was inductive reasoning. Even so, this simple method – which uses sets of critical questions to check if one’s conclusions are based on valid premises – irrevocably changed the very way we think about truth and knowledge.

In practice, the Socratic method worked like this. After calling for a definition of a large idea – say, justice – Socrates would then ask his respondent several related questions and demand a brief and concise answer to each of them, usually either a “yes” or a “no.” Having obtained a number of apparently disconnected answers in this way, he would then compare the answers to one another and “syllogize” them to demonstrate that they refute the respondent’s original definition. “Never a teacher of anybody” by his own admission, Socrates’ objective was solely to examine the incompleteness of the proposed definition, not to offer a new one. Not only did he never claim to understand the idea behind it, but he also asserted that – for all he knew beforehand – his questions might have led to the confirmation rather than the refutation of the answer given.

Socrates’ victims didn’t buy any of this. Instead, they considered his method confusing and called him “sly” for refusing to give answers himself and for pretending to know less than what he actually knew. Interestingly, the Ancient Greek word for “slyness” is a variant of the word “irony,” which originally meant “asking questions.” Hence, Socrates is responsible for the origin of the modern conception of irony as the conveyance of a statement by words which literally express the contradictory meaning.

Socratic religion: the big turn

Behind the Socratic method, says famous historian of culture Will Durant, “there was a philosophy – elusive, tentative, unsystematic, but so real that in effect the man died for it. At first sight, there is no Socratic philosophy; but this is largely because Socrates, accepting the relativism of Protagoras, refused to dogmatize, and was certain only of his ignorance.” Now, this Protagoras that Durant mentions was an older contemporary of Socrates who created a major controversy in Ancient Athens when he said that man was the measure of all things and that, as far as gods were concerned, it was impossible to know if they existed or not. It was Socrates who really understood what Protagoras actually meant. In doing so, he became the first real moral philosopher in the history of humankind.

You see, most philosophy before Socrates was either metaphysical or cosmological in that it dealt exclusively with big questions such as the origins of the universe or the fundamental nature of reality. Socrates did not even discuss such topics. On the contrary, he argued that anyone who troubled their mind with nebulous problems such as “the Nature of the Universe” was either a fraud or a madman. Just like Confucius in China, Socrates enjoyed asking his followers if they supposed their knowledge of human affairs was so complete that they felt ready to seek new fields for the exercise of their brains and meddle with the affairs of the gods. If they answered yes, he was quick to demonstrate their folly by pointing out the absurdity and immorality of the conventional epic accounts of the gods.

Of the gods, Socrates insisted that he knew nothing. He, says Xenophon, was “always conversing about human things only – examining what is pious and impious; what is beautiful and what is ugly; what is just and unjust; what is courage and what is cowardice; what is a city, what is a statesman, and what rule over human beings may be considered skilled and just. These were the problems Socrates discussed with other people, believing only the knowledge of such issues can make one a noble and pious person, whereas ignorance – an irreverent slave.” Here we can observe the real nature of what historians sometimes refer to as “Socratic religion.” For Socrates, asceticism, rituals and sacrifices aren’t the essence of our service to the gods; wisdom and moral virtue are. What is good and holy, he argues memorably in Plato’s dialogue “Euthyphro,” isn’t good or holy because it is beloved by the gods; rather, it is beloved by the gods because it is good and holy in itself.

Socratic ethics: virtue is knowledge

In proposing that what is good isn’t actually determined by the gods but merely recognized by them, Socrates initiated a philosophical revolution. Most religions, even today, equate being good with being a devotee. In Christianity, you can’t just obey the Great Commandments: to enter the kingdom of heaven, you have to accept Christ as your personal savior as well. “Only those who believe and are baptized will be saved,” says Jesus in Mark 16:16, “and those who don’t believe will be condemned for all eternity.” Put otherwise, morality has a supernatural basis and the ways of God lie beyond human understanding. When God asks Abraham to sacrifice his only son, Abraham’s job is not to question God’s command, but merely to obey it. He is, after all, a mere mortal. Only God can decide what is good and what is not.

Well, says Socrates, that’s not precisely right. Gods don’t get to decide what is good and what is bad: they merely know more than humans and can discern better between the two. That is to say, goodness doesn’t come from the gods – its existence actually precedes theirs. Gods are good not because they possess something that can be described as “goodness,” but because they know everything and, thus, know which action is good and which one is bad. Our job is to follow their suit. The more we know about ourselves and our actions, says Socrates, the better we can become, and the closer we can get to what the gods are. Neither piety nor virtue stems from belief – both of them are daughters of wisdom. To rephrase English poet Alfred Tennyson, ours isn’t just to do and die, but, on the contrary, to reason why.

Basically, for Socrates, morality and knowledge are one and the same thing. The only way to do good in life is to know what good is beforehand. And the only way to discover what good is, is through questioning and reasoning. Without proper knowledge, right action is impossible; with it – it is inevitable. “Virtue is knowledge,” insists Socrates, adding, even more famously, that “no one does wrong willingly.” Acting against one’s better judgment is impossible. To know something – and to really know it – is the same as to possess it completely. To turn this on its head, people who claim to know things but act in their defiance actually don’t know the things in question. If, for example, one truly believed that God was all-powerful and all-seeing, then they would never do anything to offend Him. However, even avowed believers lapse repeatedly because, in reality, nobody knows if there is a God or not. People who say otherwise aren’t smart – but dishonest.

The death of Socrates

If knowledge is virtue, argued Socrates, then democracy must be a failed concept. “It is absurd,” he supposedly said once, “to appoint public officials by lot, when none would choose a pilot or builder or flautist by lot, nor any other craftsman even for work in which mistakes are far less disastrous than mistakes in statecraft and government.” It was owing to ideas such as this that the majority of wealthy Athenians and Athenian politicians looked upon Socrates with annoyance and suspicion. After all, those in power are always in favor of the status quo. Socrates was anything but. He firmly believed that only a government chosen by knowledge and ability could save Athens. He also wasn’t afraid to make his opinions publicly known.

One day in 399 B.C., a rich and socially prominent politician named Anytus convinced the poet Meletus and the rhetorician Lycon to bring charges against Socrates “for corrupting the young men and not believing in the gods of the city.” As related by Plato in his “Apology,” Socrates’ defense speech at the trial was not in the least conciliatory. Rather than accepting a financial fine, he proposed that the city should, instead, pay him for his valuable service. “You will not easily find another one like me,” he said, “for I am a sort of a gadfly, given to the state by God himself. And the state is like a great and noble horse who is tardy in his motions, owing to his very size, and requires to be stirred into life. And so I am that gadfly which God has given the state and all day long am always fastening upon you, arousing and persuading and reproaching you.”

Unsurprisingly, Socrates was eventually condemned to death. Even then, he didn’t flinch. “There is great reason to hope that death is good,” he said after hearing the verdict, “for it is one of two things: either a state of nothingness and utter unconsciousness, or, as men say, migration of the soul from this world to another.” For Socrates, both were great outcomes. If the former, then “eternity was only a single night” and “the joys of all earthly days are incomparable to the bliss of a calm and peaceful sleep.” If the latter, then Socrates was about to meet some of the most famous people in history and be able to have conversations with them for all eternity. “What would not a man give if he might converse with Orpheus and Hesiod and Homer?” he asked his prosectures. “Nay, if this be true, let me die again and again.”

It would have been easy to escape from the Athenian prison. Crito, an old friend of Socrates, bribed the jailer and begged the philosopher to flee his cell. Socrates, however, refused. “I promised in word to obey the laws of Athens,” he told Crito, “and I intend to deliver on this promise in deed.” According to Plato’s dialogue “Phaedo,” Socrates spent the last hours in his cell, among his disciples, in discussion of the immortality of the soul and the task of philosophy to free it from the confines of the body. Afterward, he solemnly took the state-prepared poison, as his friends wept and sat helplessly by. “Crito, we owe a cock to the god Asclepius,” Socrates whispered. “Please, pay him and do not neglect the task. “It shall be done,” replied Crito. “Is there anything else you need me to do?” No answer came back.

The legacy of Socrates

“The perennial fascination of Socrates,” writes Christopher Charles Taylor in Gale’s “Encyclopedia of Philosophy,” “owes less to any specific doctrines than to Plato’s portrayal of him as the exemplar of a philosophical life – that is, a life dedicated to following the argument wherever it might lead, even when it, in fact, led to hardship, poverty, judicial condemnation, and consequent death. Plato’s depiction of how Socrates lived for philosophy would, in any case, have made him immortal; his presentation of how he died for it has given him a unique status in its history.” Plato’s dialogues, agrees Richard Robinson, “made Socrates the chief martyr of reason just as the gospels made Jesus the chief martyr of faith.”

Indeed, Socrates made more converts to his philosophy with his impeccable life and glorious death than with any of his words and arguments. “Through his pupils,” writes Will Durant, “the many suggestions of his thought became the substance of all the major philosophies of the next two centuries. The most powerful element in Socrates’ influence was the example of his life and death. He became for Greek history a martyr and a saint; and every generation that sought an exemplar of simple living and brave thinking turned back to nourish its ideals with his memory.” “In contemplating the man's wisdom and nobility of character,” wrote Xenophon, "I find it beyond my power to forget him, or, in remembering him, to refrain from praising him. And if, among those who make virtue their aim, anyone has ever been brought into contact with a person more helpful than Socrates, I count that man worthy to be called most blessed.”

More than two millennia after Socrates, probably having him in mind, Danish existentialist Søren Kierkegaard wrote that if one wants to meet a true philosopher, they will be much better looking around fireplaces, artisan shops or public squares than at schools or universities. Echoing the same conviction, Friedrich Nietzsche memorably remarked that only philosophers who teach by example can be worthy of respect. Socrates is widely considered not only the first, but also the most famous champion of this idea – namely, that philosophy is not something one teaches through words, but something one demonstrates through deeds. As an argument in favor of this view, he left us neither books nor manuscripts. He did leave us something far more valuable, though: his own life.

Sources

Ancient sources

*All available in numerous English translations.

- Aristotle, Metaphysics.

- Diogenes Laërtius, “Plato,” Lives of Eminent Philosophers.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece.

- Plato, Apology.

- Plato, Crito.

- Plato, Euthyphro.

- Plato, Laches.

- Plato, Letters.

- Plato, Phaedo.

- Plato, Phaedrus.

- Plato, Symposium.

- Xenophon, Apology of Socrates.

- Xenophon, Memorabilia.

Modern sources

- Vitomir Mitevski, Socrates (Skopje: Matica, 2008) [Витомир Митевски, Сократ (Скопје: Матица, 2008)].

- C. C. W. Taylor, “Socrates,” in: Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol. IX [Donald M. Borchert, ed.], 2nd edn (Gale, 2006), pp. 105-114.

- Will Durant, “Socrates (1452-1482),” in: The Story of Civilization, Vol. II: The Life of Greece (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961), pp. 364-373.

- Richard Robinson, “Socrates (469-399 BC),” in: The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy (Jonathan Rée and J. O. Urmson, eds.), 3rd edn (London and New York, Routledge, 2005), pp. 358-361.

- “Socrates: The Life Which Is Unexamined Is Not Worth Living,” in: The Philosophy Book (New York: DK), pp. 46-49.